Back in 2012, the speaker at the University of Nevada, Reno Foundation’s annual banquet was Charles Duhigg of the New York Times, author of the book The Power of Habit. What he described in his talk (and in more detail in the book) had to do with why people do what they do over and over again, and how they can change old habits or learn new ones. He outlined the system of “cue, routine, reward” as a means by which behaviors are continually reinforced, and he offered the following framework for change:

Identify the routine

Experiment with rewards

Isolate the cue

Have a plan

As I sat listening to his talk, I recognized what he was describing as essentially being what psychologists and behaviorists refer to as operant conditioning.

While I had been exposed to the idea of operant conditioning in classes before, though, the truth is that I hadn’t really thought through all of the implications of its practical applications until nine years ago, when I adopted a dog from the humane society. I took her to training classes with varying degrees of success and looked for various resources online. I sometimes heard people refer to “clicker training,” but didn’t know exactly what it was or how it worked until, after having done a little research, I bought a book about it online.

The book explained the theory of operant conditioning and said that clicker training had been used to train dolphins and other marine mammals. The book also explained the idea of “shaping” and it described in detail the steps one could take to teach dogs various kinds of tricks. I was intrigued, so I got a clicker and started trying it out.

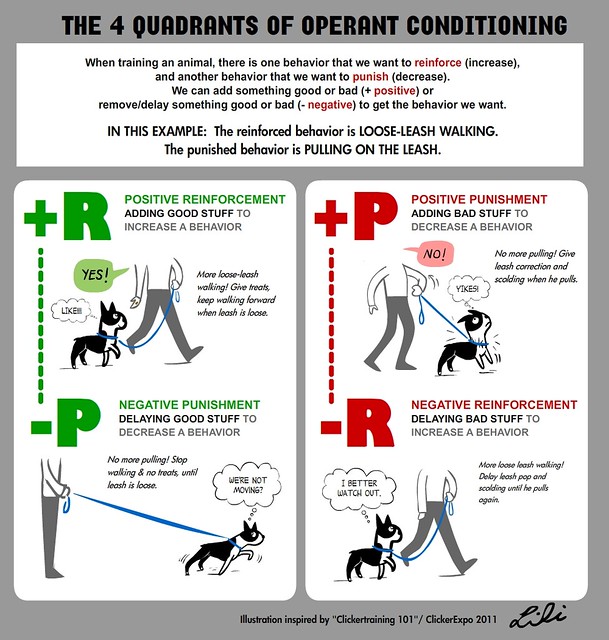

Although technically all dog training is based on the theory of operant conditioning, as explained in the infographic below, clicker training is primarily a form of positive reinforcement, so it is focused on the left side of the quadrant. By contrast, traditional dog training usually involves more of a mix of both positive reinforcements and positive punishments.

Using the clicker as a form of positive reinforcement provides a way of communicating with the dog to encourage more of certain behaviors. As the dog figures this out, he or she will start offering up all sorts of behaviors that have been rewarded in the past.

With a little creativity and patience, people can begin to figure out how to break behaviors down into manageable steps as a way of teaching the dog something new. When you want to train a new behavior, you only reward the steps that lead to that behavior as a way of shaping a new behavior. It certainly takes patience, but when applied regularly and diligently, it can achieve amazing results.

We’ve all heard the expression “herding cats,” but as demonstrated in the video below, clicker training can work for both dogs and cats as a way of shaping behaviors.

So what does all this have to do with the topics I usually write about: prospect development, data analytics, research, and management? Everything. If we can understand how to use positive reinforcement to shape and develop new behaviors in dogs or cats, then we can certainly think through its implications for ourselves and those we work with.

In an earlier post, I cited Scott Adams on the importance of systems over goals; I’m pretty sure that he’d agree that a good understanding of the applicability of operant conditioning to many situations is a necessary prerequisite for a good system. One of the reason that the situations in his comic strip Dilbert are as amusing as they are is that the systems at work in Dilbert’s workplace are set up to reward the most peculiar things, and so those things keep happening.

How have you used operant conditioning to shape behaviors in the past? Perhaps you’ve applied it in your own life, or to teach a dog or cat a new trick, or to train someone at work. And if you’re not sure if you’ve ever consciously applied it before, can you think of some situations in which you would like to try it? I’m interested in reading your comments below.